Abu Simbel temples refers to two massive rock temples in Abu Simbel (أبو سمبل in Arabic) in Nubia, southern Egypt on the western bank of Lake Nasser about 230 km southwest of Aswan (about 300 km by road). The complex is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the "Nubian Monuments,"which run from Abu Simbel downriver to Philae (near Aswan).

A scale model showing the original and current location of the temple (with respect to the water level)

The twin temples were originally carved out of the mountainside during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II in the 13th century BC, as a lasting monument to himself and his queen Nefertari, to commemorate his alleged victory at the Battle of Kadesh, and to intimidate his Nubian neighbors. However, the complex was relocated in its entirety in 1968, on an artificial hill made from a domed structure, high above the Aswan High Dam reservoir.

Close-up of one of the colossal statues of Ramesses II, wearing the double crown of Lower and Upper Egypt

The relocation of the temples was necessary to avoid their being submerged during the creation of Lake Nasser, the massive artificial water reservoir formed after the building of the Aswan High Dam on the Nile River. Abu Simbel remains one of Egypt's top tourist attractions.

History

Construction

Construction of the temple complex started in approximately 1244 BCE and lasted for about 20 years, until 1224 BCE. Known as the "Temple of Ramesses, beloved by Amun," it was one of six rock temples erected in Nubia during the long reign of Ramesses II. Their purpose was to impress Egypt's southern neighbors, and also to reinforce the status of Egyptian religion in the region. Historians say that the design of Abu Simbel expresses a measure of ego and pride in Ramesses II.

The collapsed colossus of the Great Temple supposedly fell during an earthquake shortly after its construction, when moving the temple it was decided to leave it as the face is missing

Rediscovery

With the passage of time, the temples fell into disuse and eventually became covered by sand. Already in the 6th century BC, the sand covered the statues of the main temple up to their knees. The temple was forgotten until 1813, when Swiss orientalist JL Burckhardt found the top frieze of the main temple. Burckhardt talked about his discovery with Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni, who travelled to the site, but was unable to dig out an entry to the temple. Belzoni returned in 1817, this time succeeding in his attempt to enter the complex. He took everything valuable and portable with him. Tour guides at the site relate the legend that "Abu Simbel" was a young local boy who guided these early re-discoverers to the site of the buried temple which he had seen from time to time in the shifting sands. Eventually, they named the complex after him.

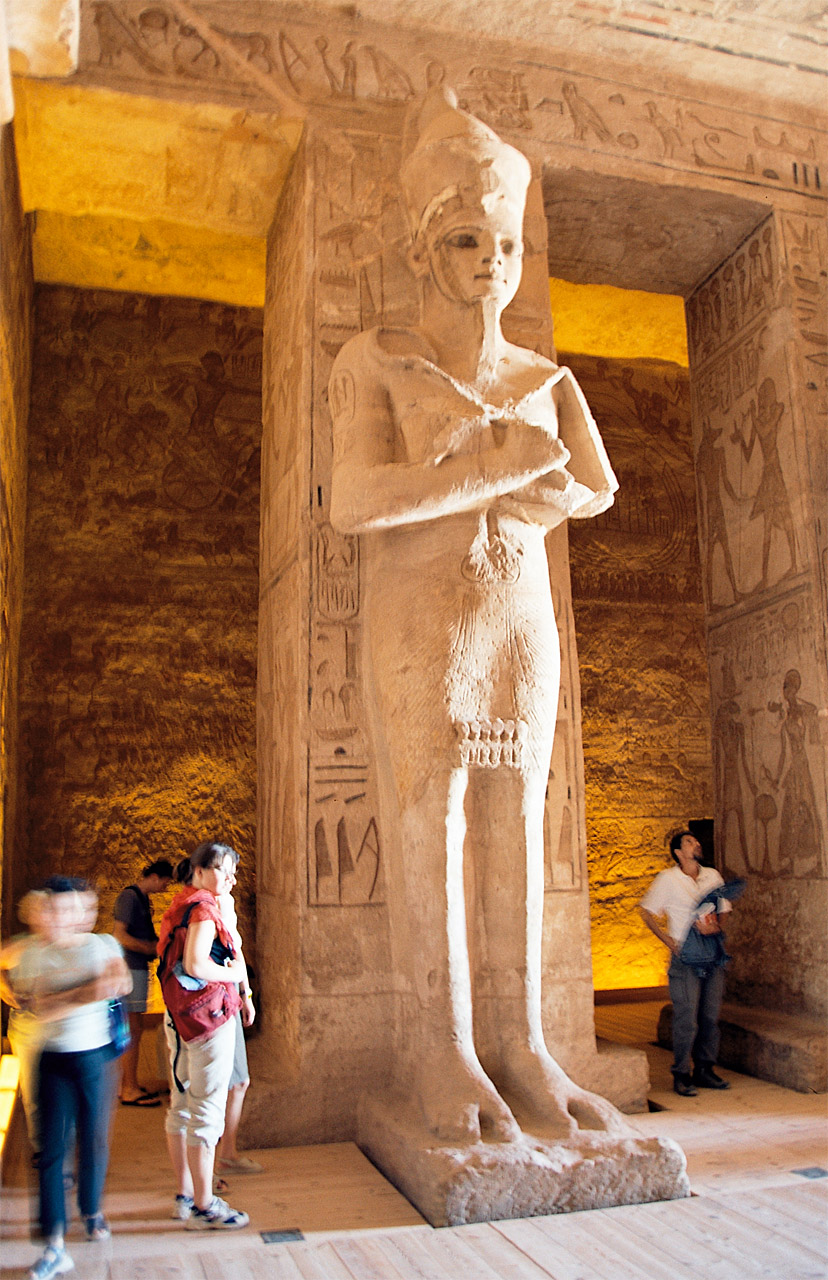

One of the eight pillars in the main hall of the temple, showing Ramesses II as Osiris

Relocation

In 1959 an international donations campaign to save the monuments of Nubia began: the southernmost relics of this ancient human civilization were under threat from the rising waters of the Nile that were about to result from the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

The gods Set (left) and Horus (right) adoring Ramesses in the small temple at Abu Simbel

One scheme to save the temples was based on an idea by William MacQuitty to build a clear fresh water dam around the temples, with the water inside kept at the same height as the Nile. There were to be underwater viewing chambers. In 1962 the idea was made into a proposal by architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry and civil engineer Ove Arup. They considered that raising the temples ignored the effect of erosion of the sandstone by desert winds. However the proposal, though acknowledged to be extremely elegant, was rejected.

Abu Simbel Temple of Ramesses II

The salvage of the Abu Simbel temples began in 1964 by a multinational team of archeologists, engineers and skilled heavy equipment operators working together under the UNESCO banner; it cost some $40 million at the time. Between 1964 and 1968, the entire site was carefully cut into large blocks (up to 30 tons, averaging 20 tons), dismantled, lifted and reassembled in a new location 65 meters higher and 200 meters back from the river, in one of the greatest challenges of archaeological engineering in history. Some structures were even saved from under the waters of Lake Nasser. Today, thousands of tourists visit the temples daily. Guarded convoys of buses and cars depart twice a day from Aswan, the nearest city. Many visitors also arrive by plane, at an airfield that was specially constructed for the temple complex.

Detail Temple of Rameses II saved from being lost beneath the River Nile

The complex consists of two temples. The larger one is dedicated to Ra-Harakhty, Ptah and Amun, Egypt's three state deities of the time, and features four large statues of Ramesses II in the facade. The smaller temple is dedicated to the goddess Hathor, personified by Nefertari, Ramesses's most beloved of his many wives. The temple is now open to the public.

Abu Simbel in the heart of Nubia, the Temple of Rameses II

The Great Temple

The Great Temple at Abu Simbel, which took about twenty years to build, was completed around year 24 of the reign of Rameses the Great (which corresponds to 1265 BCE). It was dedicated to the gods Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah, as well as to the deified Rameses himself. It is generally considered the grandest and most beautiful of the temples commissioned during the reign of Rameses II, and one of the most beautiful in Egypt.

Baboon carvings above the heads of the statues of Ramses

Four colossal 20 meter statues of the pharaoh with the double Atef crown of Upper and Lower Egypt decorate the facade of the temple, which is 35 meters wide and is topped by a frieze with 22 baboons, worshippers of the sun and flank the entrance.[6] The colossal statues were sculptured directly from the rock in which the temple was located before it was moved. All statues represent Ramesses II, seated on a throne and wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. The statue to the left of the entrance was damaged in an earthquake, leaving only the lower part of the statue still intact. The head and torso can still be seen at the statue's feet.

Next to the legs of the colossi, there are other statues no higher than the knees of the pharaoh. These depict Nefertari, Ramesses's chief wife, and queen mother Mut-Tuy, his first two sons Amun-her-khepeshef, Ramesses, and his first six daughters Bintanath, Baketmut, Nefertari, Meritamen, Nebettawy and Isetnofret.

Nefertari's Temple at Abu Simbel

The entrance itself is crowned by a bas-relief representing two images of the king worshiping the falcon-headed Ra Harakhti, whose statue stands in a large niche. This god is holding the hieroglyph user in his right hand and a feather while Ma'at, (the goddess of truth and justice) in on his left; this is nothing less than a gigantic cryptogram for Ramesses II's throne name, User-Maat-Re. The facade is topped by a row of 22 baboons, their arms raised in the air, supposedly worshipping the rising sun. Another notable feature of the facade is a stele which records the marriage of Ramesses with a daughter of king Hattusili III, which sealed the peace between Egypt and the Hittites.

The inner part of the temple has the same triangular layout that most ancient Egyptian temples follow, with rooms decreasing in size from the entrance to the sanctuary. The temple is complex in structure and quite unusual because of its many side chambers. The hypostyle hall (sometimes also called pronaos) is 18 meters long and 16,7 meters wide and is supported by eight huge Osirid pillars depicting the deified Ramses linked to the god Osiris, the god of the Underworld, to indicate the everlasting nature of the pharaoh.

The colossal statues along the left-hand wall bear the white crown of Upper Egypt, while those on the opposite side are wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt(pschent). The bas-reliefs on the walls of the pronaos depict battle scenes in the military campaigns the ruler waged. Much of the sculpture is given to the Battle of Kadesh, on the Orontes river in present-day Syria, in which the Egyptian king fought against the Hittites. The most famous relief shows the king on his chariot shooting arrows against his fleeing enemies, who are being taken prisoner. Other scenes show Egyptian victories in Libya and Nubia.

Solar phenomena

It is believed that the axis of the temple was positioned by the ancient Egyptian architects in such a way that on October 21 and February 21 (61 days before and 61 days after the Winter Solstice), the rays of the sun would penetrate the sanctuary and illuminate the sculptures on the back wall, except for the statue of Ptah, the god connected with the Underworld, who always remained in the dark.

These dates are allegedly the king's birthday and coronation day respectively, but there is no evidence to support this, though it is quite logical to assume that these dates had some relation to a great event, such as the jubilee celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of the pharaoh's rule.

In fact, according to calculations made on the basis of the heliacal rising of the star Sirius (Sothis) and inscriptions found by archaeologists, this date must have been October 22. This image of the king was enhanced and revitalized by the energy of the solar star, and the deified Ramesses Great could take his place next to Amun Ra and Ra-Horakhty.

Due to the displacement of the temple and/or the accumulated drift of the Tropic of Cancer during the past 3,280 years, it is widely believed that each of these two events has moved one day closer to the Solstice, so they would be occurring on October 22 and February 20 (60 days before and 60 days after the Solstice, respectively).

The NOAA Solar Position Calculator may be used to verify the declination of the Sun for any location on Earth, at any particular date and time. For the latitude of Abu Simbel 22°20′13″N 31°37′32″E / 22.33694°N 31.62556°E / 22.33694; 31.62556, the calculator will yield values close to -11º for both Oct 22 and Feb 20.

The Small Temple

The temple of Hathor and Nefertari, also known as the Small Temple, was built about one hundred meters northeast of the temple of Ramesses II and was dedicated to the goddess Hathor and Ramesses II's chief consort, Nefertari. This was in fact the second time in ancient Egyptian history that a temple was dedicated to a queen. The first time, Akhenaten dedicated a temple to his great royal wife, Nefertiti. The rock-cut facade is decorated with two groups of colossi that are separated by the large gateway. The statues, slightly more than ten meters high, are of the king and his queen.

On either side of the portal are two statues of the king, wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt (south colossus) and the double crown (north colossus); these are flanked by statues of the queen and the king. What is truly surprising is that for the only time in Egyptian art, the statues of the king and his consort are equal in size. Traditionally, the statues of the queens stood next to those of the pharaoh, but were never taller than his knees. This exception to such a long standing rule bears witness to the special importance attached to Nefertari by Ramesses, who went to Abu Simbel with his beloved wife in the 24th year of his reign.

As the Great Temple of the king, there are small statues of princes and princesses next to their parents. In this case they are positioned symmetrically: on the south side (at left as you face the gateway) are, from left to right, princes Meryatum and Meryre, princesses Meritamen and Henuttawy, and princes Rahirwenemef and Amun-her-khepeshef, while on the north side the same figures are in reverse order. The plan of the Small Temple is a simplified version of that of the Great Temple.

As the larger temple dedicated to the king, the hypostyle hall or pronaos is supported by six pillars; in this case, however, they are not Osirid pillars depicting the king, but are decorated with scenes with the queen playing the sinistrum (an instrument sacred to the goddess Hathor), together with the gods Horus, Khnum, Khonsu, and Thoth, and the goddesses Hathor, Isis, Maat, Mut of Asher, Satis and Taweret; in one scene Ramesses is presenting flowers or burning incense.The capitals of the pillars bear the face of the goddess Hathor; this type of column is known as Hathoric.

The bas-reliefs in the pillared hall illustrate the deification of the king, the destruction of his enemies in the north and south (in this scenes the king is accompanied by his wife), and the queen making offerings to the goddess Hathor and Mut. The hypostyle hall is followed by a vestibule, access to which is given by three large doors. On the south and the north walls of this chamber there are two graceful and poetic bas-reliefs of the king and his consort presenting papyrus plants to Hathor, who is depicted as a cow on a boat sailing in a thicket of papyri. On the west wall, Ramesses II and Nefertari are depicted making offerings to god Horus and the divinities of the Cataracts — Satis, Anubis and Khnum.

The rock cut sanctuary and the two side chambers are connected to the transverse vestibule and are aligned with the axis of the temple. The bas-reliefs on the side walls of the small sanctuary represent scenes of offerings to various gods made either by the pharaoh or the queen. On the back wall, which lies to the west along the axis of the temple, there is a niche in which Hathor, as a divine cow, seems to be coming out of the mountain: the goddess is depicted as the Mistress of the temple dedicated to her and to queen Nefertari, who is intimately linked to the goddess.

Each temple has its own priest that represents the king in daily religious ceremonies. In theory, the Pharaoh should be the only celebrant in daily religious ceremonies performed in different temples throughout Egypt. In reality, the high priest also played that role.

To reach that position, an extensive education in art and science was necessary, like the one pharaoh had. Reading, writing, engineering, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, space measurement, time calculations, were all part of this learning. The priests of Heliopolis, for example, became guardians of sacred knowledge and earned the reputation of wise men.

No comments:

Post a Comment